Election integrity was the esprit de corps behind the efforts of seven troubled citizens from Williamson County, TN. Their concerns over the November election motivated their actions--especially because Williamson County uses Dominion Voting machines.

Starting in January, they began to look at ways to make elections more secure in their county—with the hope that their efforts would someday be a blueprint for the state. The team calls itself the Williamson County Voters For Election Integrity (WCV).

Some of the team members wish to remain anonymous; therefore, some will be referenced by their function in the group.

The citizen team of businesspeople, a librarian, and IT professionals has taken a deep dive into every aspect of the voting process, end-to-end, pouring over materials, laws, and processes.

In May, they had the opportunity to meet Arizona's state Rep. Mark Finchem for a few hours one evening. He had traveled to Tennessee for the express purpose of showing citizens that local action can change the way elections are run. He loaned them the watermarked, secure ballot he is now shopping in Arizona, which he calls the Arizona Ballot Integrity Project. It was a real turning point for the team.

One of the masterminds behind the Williamson County group, Kathy Harms, told UncoverDC that Finchem's insights were critical. His input helped them fast-track their thought process and decision-making.

On Wednesday evening, with 9 months of inquiry and analysis under their belts, they held a public meeting in Franklin, TN, to show what they have found. First, they spoke about what they have done. Below, in slide one of the presentation, they demonstrate just how serious they were in their pursuit:

-

- Reviewed reports about machines, ballots, voting processes, nullification of legislators and voting laws, court cases, Big Tech/media censorship

- Evaluated affidavits, data presentations, documentaries, Dominion User manuals

- Interviewed poll workers

- Attended open meetings

- Presented their findings to legislators, government officials, and the public

The goal in their undertaking is "to ensure that their county has in the future, a safer, more secure, comprehensive voting model that bolsters election integrity in Tennessee elections." Their vision is to make their recommendations stick and model how elections should be run in all 95 counties.

They found several concerning vulnerabilities. They confirmed that the Dominion Voting Machines are vulnerable to hacking. They also confirmed that the security standards had been completely ignored. They explained that "current voting machines in Tennessee are required by the Election Assistance Commission (EAC) to only be certified up to 2005 security standards, criteria that were in place two years before the first smartphone was invented."

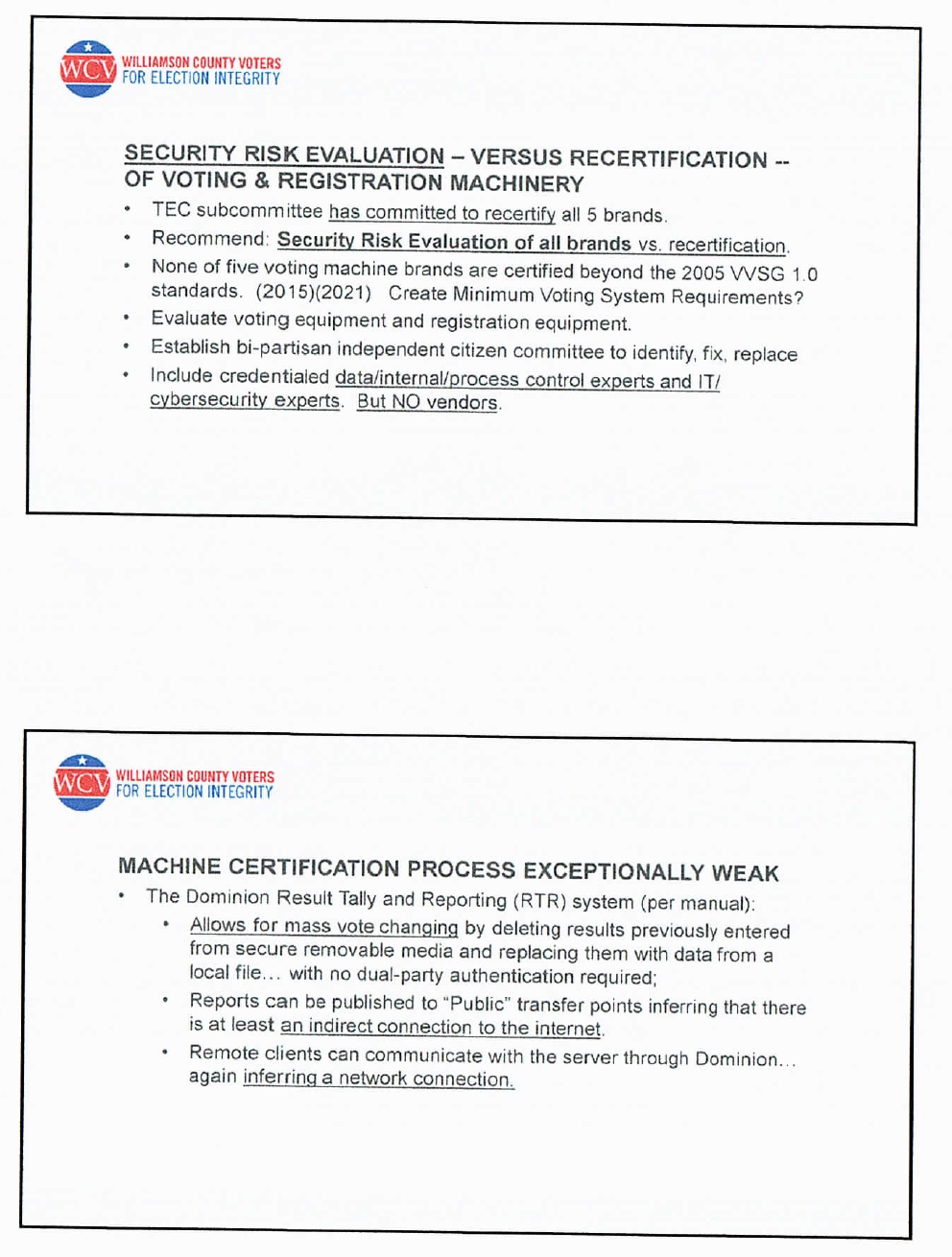

Notably, the State Election Commission has committed to performing recertification on all five brands and versions of the machines used in Tennessee. The team noted, however, that recertification would not be enough to address what they have found. Frank Limpus, one of the team members, states:

A security risk evaluation absolutely needs to be done on both the precinct voting and registration equipment and measured against some form of the 2021 Voluntary Voting System Guidelines (VVSG 2.0), first produced in 2002 by the bipartisan Commission on Federal Election Reform established under the EAC. And the evaluation needs to be done by a bipartisan and independent citizen committee composed of data/internal/process control experts as well as IT/cybersecurity experts. This particular audit should be the compelling decision point on retaining or adding any voting machine vendor in Tennessee. Right now, it’s not.

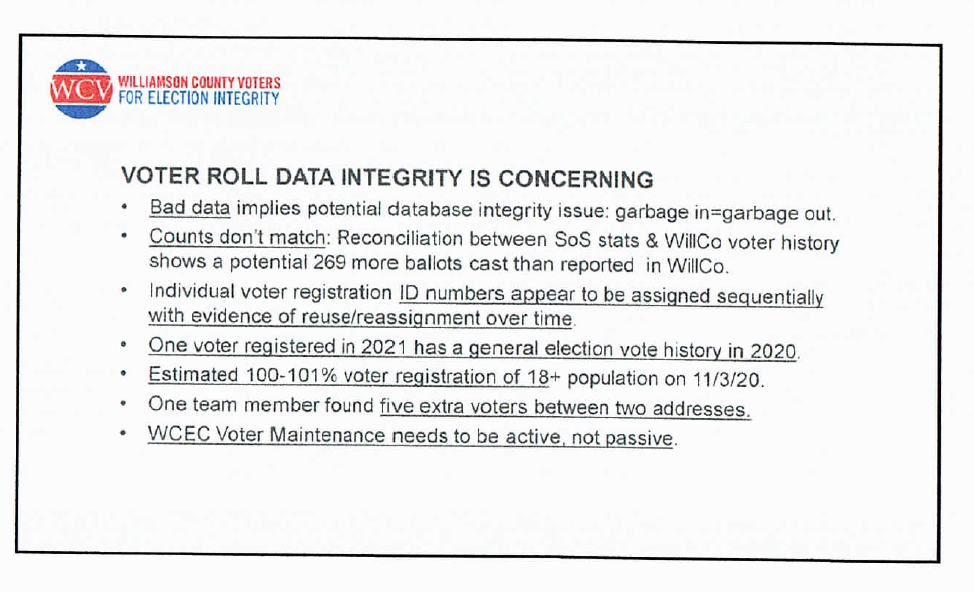

Dominion/Security

Dominion/Security

They also found that legislators and government officials were overconfident in the audit process, which is weak and of very little material use. The team has found that many legislators and commissioners in Tennessee simply do not believe that Tennessean elections are at risk for fraud. Audits are not taken seriously in the state.

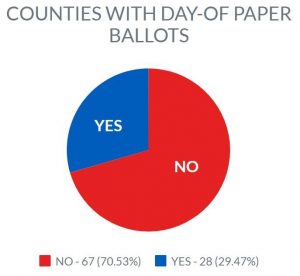

Harms and her team found that 70 percent of Tennessee counties cannot be audited properly because there are no paper ballots. The majority of Tennessee voting, they say, is done on Direct-Recording Electronic (DRE) voting machines without paper ballots to verify the voter's choices.

Counties with Paper Ballots/WVV

Counties with Paper Ballots/WVV

Blue triangles denote counties with paper ballots. Red denotes those that do not use paper ballots. 67 of 95 counties in Tennessee do not allow for a post-election audit of ballots.

The team confirmed that Ballot Marking Devices (BMD):

-

- Can be hacked, misconfigured, or contain malware.

- Create longer voting lines and are twice the cost of paper ballots.

- Rely on voters detecting ballot error, yet only 5-7% of voters find and report errors.

- Can show one thing on a screen and print something different

- Voters do not trust BMD's and do not want unnecessary technology in their elections.

An impressive part of their process was the detailed analysis of what they call "the front door" of election integrity—the data collection and maintenance of the voter rolls.

Dirty voter rolls have long been responsible for fraud in elections. A young, data-savvy librarian (MSLIS) with a decade of experience in libraries, information, and software development was in charge of that part of the project.

Among her recommendations were:

-

- Check for transients, people moving in and out of the county more carefully

- The change list maintenance program should be run annually

- Develop better minimum voter registration software standards, checking for functionality

- Data logic checks

- Fraud detection and pattern analysis

- Retain all refinement changes for two years

- Look at county tax files and death records in county and compare to the Master Death File one level up

- Look at Tennessee Bureau of Investigation for criminal records, names, citizenship status that would disqualify a voter.

The second step in the "front door" part of the voting process involves what happens with a voter at the polls. This is the step where precincts can more robustly secure the voter registration process. Things like--ensuring that voting takes place at precincts, not voting centers, eliminating a need for an internet connection on the day-of-vote registration, and going offline where you can in the voting process to prevent hacking and security breaches.

One of the most important points in the presentation was highlighted by the librarian/data analyst. She spoke about the importance of Unique Non-Sequential Voter Registration IDs:

"From what I can see, Voter Registration IDs are assigned sequentially (e.g., everyone registering in 2021 are all one after the other when sorted by registration date) and have the potential to be reused (e.g., see a voter with newer registration date, but their Voter ID falls in sequence with groups of voters who registered several years before). This is poor design - both from a security perspective and a functional perspective."

The team emphasized that local control of precinct data is critical. Voter centers are "not worth the risk that their convenience affords."

"With all of the voter check-in online, it is vulnerable to hacking and real-time monitoring. [Nefarious actors] can do a lot with real-time monitoring. They can see how many people have voted, how many are left to vote, that's a really important thing—as well as the specific people who did vote. That's a lot of powerful data that can be used to understand who's voting, how a precinct is voting, and to do targeted attacks."

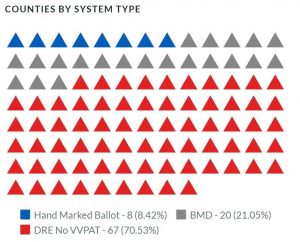

Some of their concerning findings on the voter rolls are pictured below:

Voter Roll/WCV

Voter Roll/WCV

The librarian also stated that the absentee ballot process has to be tightened. She did not recommend completely removing voter registration software. However, she said, "it should not be online at all times."

Secure Voter Registration/WCV

Secure Voter Registration/WCV

According to this group, a secure, randomized ID, watermarked-UV light-reactive ballot like the one proposed by Rep. Finchem is a critical piece in the quest for election integrity. And the ability to self-adjudicate a ballot rejected by a tabulator is key.

Current Dominion Optical scanners allow the voter to perform their own adjudication, eliminating tampering at that stage of the voting process. They recommended the cross-referencing of precinct tallies with county and state totals. It should be, they said, a secure process from beginning to end.

"Passwords managed by users must be unique, required change on first login, and if compromised. County election officials must "ensure sufficient resources/staff are trained to operate election system fully, without machine vendor presence or interaction with the system," the team recommended.

Notably, in Williamson County, the Dominion employee was the only one trained to interact with the system, just as seen in multiple other instances across the country on November 3.

Election audits were under scrutiny by this team as well. In Tennessee, 70 percent of counties are not audited or auditable. Of those audited, the team says, only one of three process functions is examined. They recommended yearly audits of county election commissions.

The result of their research found that a good audit should, at a minimum, answer these questions:

-

- Does the ballot scan code represent the voter's vote?

- Does the tabulator correctly record and count the voters' ballots?

- Does the report system correctly tally tabulator votes?

Learning lessons from the November election, the WCV team recommended some best practices for elections rules and laws:

Best Practices/WCV

Best Practices/WCV

Where does this project go next? Kathy Harms told UncoverDC that she hopes their hard work will be put to good use:

"The grassroots people want more confidence in our elections. We are going to be asking legislators and election commissioners to listen to their constituents and make the recommended changes."