The Eric Swalwell story travels effortlessly, like a rinky-dink origami sailboat cascading down a street-gutter stream. Swalwell, each time his mug appears in the press is inspiration to every average-looking dude (such as myself) that under the right circumstances romance might be found with a good-looking Asian girl, reminiscent perhaps of the anime girls that some average-looking dudes have fixated on in their lives.

Various profiles have been written of Swalwell’s career. The typical account being the victory that sent him to Congress, a win over nearly decrepit 80-year-old congressman and fellow Democrat Pete Stark. Following that rags-to-riches chapter, the Swalwell story generally jerks forward in time and undresses itself to reveal the heart of the journalistic effort: Swalwell’s sexual relationship with Chinese spy Christine Fang. I can hardly argue this framing of the Swalwell story or the attraction of Penthouse Letters.

What is left out of the Swalwell story, however, is what interests me (now that I’m satisfied that I’ve seen every seductive photograph taken of Fang Fang which is publicly available), namely the sorts of hijinks that take place during political campaigns and may have taken place, specifically, during the less-written-about Swalwell campaigns that followed his run against Stark. I’ve done interviews to construct this article with Swalwell challengers Danny Reid Turner (2016) and Rudy L. Peters Jr. (2018), likely the two most compelling personal stories among Swalwell’s bi-yearly contests. Before moving on to their two races, however, a summation of Swalwell’s run against Stark is in order. A cursory look at the Stark/Swalwell race may leave you with some begrudging respect for the young Eric.

What is left out of the Swalwell story, however, is what interests me (now that I’m satisfied that I’ve seen every seductive photograph taken of Fang Fang which is publicly available), namely the sorts of hijinks that take place during political campaigns and may have taken place, specifically, during the less-written-about Swalwell campaigns that followed his run against Stark. I’ve done interviews to construct this article with Swalwell challengers Danny Reid Turner (2016) and Rudy L. Peters Jr. (2018), likely the two most compelling personal stories among Swalwell’s bi-yearly contests. Before moving on to their two races, however, a summation of Swalwell’s run against Stark is in order. A cursory look at the Stark/Swalwell race may leave you with some begrudging respect for the young Eric.

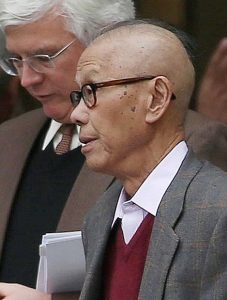

Pete Stark was described as having been, in 2012, out-of-touch, a possible contender to respected-elder status in the democrat party except that he was prone to baseless accusations against adversaries and was only barely tolerated by other senior democrats. Stark employed a strategy common to incumbents in strategically refusing his challenger a chance to debate him, allowing the upstart Swalwell an opportunity to set himself apart from usual novice; Swalwell embarrassed Stark by conducting a fake debate with a man costumed to look like Stark. However, the killing blow to the Stark machine may have been Stark’s baseless charge that Swalwell had accepted bribes from a property developer. When Stark was called out for his mud-slinging, he backed off, tacitly admitting that he was, in fact, the parody of a candidate he was portrayed as being, a doddering creature of momentum given to mush-mouthed insults that he couldn’t back up.

All in all, the Stark/Swalwell race reduced to its most interesting turns could make for a neat Cinderella screenplay. The cracks in its foundation wouldn’t show up until years later. The property developer, James Tong, who was accused of bribing Swalwell? Tong would, in fact, be sentenced in 2020 for making illegal contributions to Swalwell. And Stark’s cheap incumbent’s ploy of refusing debate to a challenger? Swalwell, once installed in office, would soon make use of the strategy himself.

In his next race in 2014, Swalwell beat Republican challenger Hugh Bussell handily with the percentage of his win being 69.8 to 30.2 percent. Following that contest, however, in 2016, Swalwell seemingly, at least to an unknowing outsider such as myself could have had a run for his money in the somewhat-unlikely Republican candidate Danny Reid Turner.

Turner was better looking than Swalwell in that same Kennedy-esque way, personable, intelligent, but I was later made to realize also had drawbacks that were common to Swalwell’s republican adversaries; Turner had a minuscule war chest as well as an uphill battle of running in California’s 15th district, an area with a heavy, almost two-to-one Democrat advantage. Turner also had a unique handicap among the club of Swalwell rivals that he was drug-addicted at the time of his campaign.

Turner was better looking than Swalwell in that same Kennedy-esque way, personable, intelligent, but I was later made to realize also had drawbacks that were common to Swalwell’s republican adversaries; Turner had a minuscule war chest as well as an uphill battle of running in California’s 15th district, an area with a heavy, almost two-to-one Democrat advantage. Turner also had a unique handicap among the club of Swalwell rivals that he was drug-addicted at the time of his campaign.

Upon hearing that a Swalwell competitor battled addiction concurrent to his attempt to unseat the strategic Swalwell, you might wonder how it was that Turner was chosen by the Republican Party to represent. One might wonder whether someone in the Swalwell camp had something to do with Turner’s selection as designated Swalwell rival. No, Turner becoming the chosen competitor was unpremeditated and a condition of chance happenings. Turner recalled to me with evident humor:

“The reality of that time in my life is I was pretty much an unemployed drug addict, and I had actually intended to run in 2018, but there was sort of, I’ll say, a wacky guy who was the chair of the Alameda County Republican Party. I’d written an email, and it was probably December of 2015, talking about some of my feelings on issues and said my intent was to run in 2018, and they came back really quickly, did an almost three or four-hour phone interview, and asked if I would run in 2016, and I (laugh) said sure.”

Turner was naturally self-deprecating in my interview with him, politically precise, scholarly, and three years sober. He also appeared to be the sort of Republican with better than a ghost of a chance in an ultra-liberal district; He talked to me about connecting with Muslim audiences at community centers where he’d been invited to speak, and he held typical RINO positions such as a coolness toward Trumpian politics and disregard for the suggestion that the 2020 election had been rigged. Many convictions Turner outlined for me were driven by numbers and statistics, which he had an amazing recall for, and he impressed me with the effort he’d put into forming his opinions even if I disagreed with one. I’d imagine he would have impressed democrats similarly. He explained the basis for his having become republican:

“The ACA was under debate my last couple years of college and I did the -- if you watch Fox News, I did the backward narrative -- because I went into school very liberal, having grown up in the Bay Area and then came out -- I studied finance and economics, and so I came out much more conservative on those aspects.”

I would have imagined Turner making a fair dent against the Swalwell machine, even considering their district’s leftward tilt. Personal issues unfortunately hobbled turner’s efforts. He said:

“I was doing door to door stuff, any speaking engagement because community organizations will host round tables, town halls, what have you, and I'd go to those any chance I got, but I did probably halt at least my efforts within the campaign for a couple months because that was actually how I started figuring out that I needed to clean up my life because I realized in June and July that, ‘Hmmm. I'm on the November ballot. I'm living more of a Hunter Biden lifestyle. I think it would be the best way to put it. If I do this long enough, I could get caught, and I'll be on CNN in a really bad way’, so I started to clean stuff up, so I'd say from July through September, I wasn't doing much on the campaign and then did a big push from September to the end of November.”

Though Turner lost to Swalwell, his numbers were in the same ballpark as the percentages achieved by Hugh Bussell, who had run against Swalwell in 2014. Bussell received 30.2 percent of the vote, and Turner received 26.2. Turner wondered aloud to me about the size of Swalwell’s war chest, and also, by contrast, discussed the micro-budget of his own effort:

“He was pretty consistent in bringing in about two million dollars (per election cycle) which is pretty decent. It's not outrageous in more populous districts. It’s kind of what you need, to have that seven figures, and two million dollars is a decent sweet spot for house races, so he's not out of the norm, but certainly, he has a very flush war chest. I'm curious where it stands after his presidential bid. Once he won in 2012 -- his fundraising numbers were lower that year because he was a challenger and money tends to follow winners -- so I'm curious because you figure 14, 16, 18, you know he took in those funds and really didn’t need to spend a penny, to be honest, and he was probably going to win the seat.

I hit one thousand dollars in funding, and so my joke was there's a big industry for campaign consulting, like there are companies and specialists that come in, and they help you run whatever, social media, print, radio, strategy and all that stuff, and one of the metrics that's pretty common is dollars per vote, like, ‘In this race, our services were able to help this candidate secure this win for two dollars a vote’, what was spent on the race. I would joke with people that I had most efficient race in the country. On the dollar per vote I was on the pennies level.”

I hope Turner, at some point in the future, reenters politics. He impressed me with gallows humor that has allowed him to roll with life’s punches. Swalwell’s following race in 2018 would be against a challenger with a more significant budget than Turner’s but, cut to the chase, 2018’s challenger Rudy Peters’ percentage of votes would barely top Turner’s. I’ll look at the 2018 Rudy Peters race in part II of this article which includes an interview with the candidate.