People profess a desire for news that isn’t racially divisive, isn’t negative, isn’t partisan, and you may be in luck; this is a story of that variety. After which, you can go right back to having CNN shovel enough coal into your furnace that you once again want to bludgeon your neighbors.

Jim Quick & Coastline and the Carolina Beach Music Festival a match made in shag heaven

Jim Quick & Coastline and the Carolina Beach Music Festival a match made in shag heaven

I recently had the opportunity to talk to career musician Jim Quick about what COVID-time has meant for live music and the prospects for live shows in the near future. His answers weren’t ones I could have thought to write and may surprise you as they did me if you expect only complaints about musicians’ lives decimated by the pandemic. His take is a lot more nuanced than that snapshot.

Jim Quick, while maybe not a household name outside of the Carolinas, typically played 250 nights per year before COVID. He is a recognized king of a regional genre of music known as “beach music,” which is heavily promoted in the Carolinas, most especially as you might imagine along the coast. I’ll get into the origin and history of beach music in a bit and its connection to race relations.

The two Carolinas had differing responses to COVID, South Carolina having a Republican governor and North Carolina a Democratic governor. North Carolina chose to shut down the live music scene almost completely, while South Carolina took a different tack and attempted to keep close to business as usual. Neither State, however, was quite the cleanly-delineated social experiment you might imagine it is.

Drum-tight North Carolina offered artists of Quick’s stature paid opportunities for virtual concerts but also had an illegal on-the-down-low concert scene that took place on farm and in field (Quick described the illegal events as “speakeasies in the woods”). Comparatively, free-wheeling, while seeming a panacea to libertarians, South Carolina often left musicians in the uncomfortable position of booking gigs based on self-estimates of the level of safety for both band and audience members. Quick described the situation to me as a moral and mental battle choosing work, and he had certainly felt COVID’s merciless effect among his acquaintances. He recalled to me,

Drum-tight North Carolina offered artists of Quick’s stature paid opportunities for virtual concerts but also had an illegal on-the-down-low concert scene that took place on farm and in field (Quick described the illegal events as “speakeasies in the woods”). Comparatively, free-wheeling, while seeming a panacea to libertarians, South Carolina often left musicians in the uncomfortable position of booking gigs based on self-estimates of the level of safety for both band and audience members. Quick described the situation to me as a moral and mental battle choosing work, and he had certainly felt COVID’s merciless effect among his acquaintances. He recalled to me,

“A lot of musician friends of mine died. I also live in Nashville, Tennessee, and I'm a writer there, and I’ve seen a lot of great writers, a lot of great musicians over there that have passed away, and a lot of my buddies in the Carolinas in the beach music industry passed with COVID. It's just been one of these things that it's just I don't know right from wrong anymore because it depends on who you talk to.”

I feel the same most of the time.

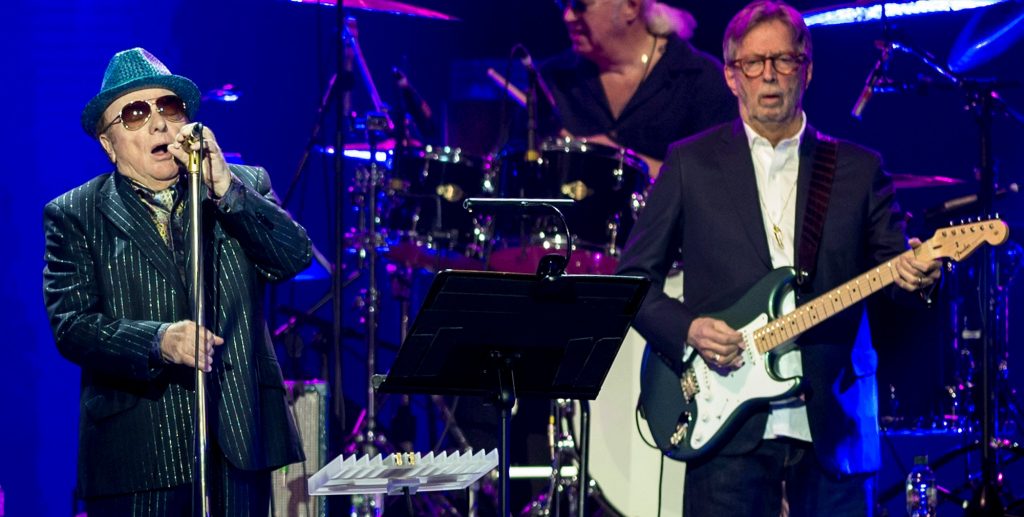

Nationally and internationally, some high-profile musicians, unlike the pragmatic Quick, took dueling uncompromising positions regarding clampdowns on the music scene, orchestrating a public feud of hot takes. In The United Kingdom, artists such as Van Morrison and Ian Brown promoted resistance to lockdowns and COVID passports, Morrison with a number of protest singles, one of which had him joined by Eric Clapton. In the U.S., Springsteen and Bon Jovi took the more conventional party line to promote masking-up.

Van Morrison, left, and Eric Clapton, shown performing at London’s O2 Arena in March 2020, have teamed up on an anti-lockdown protest song. (Gareth Cattermole / Getty Images)

Van Morrison, left, and Eric Clapton, shown performing at London’s O2 Arena in March 2020, have teamed up on an anti-lockdown protest song. (Gareth Cattermole / Getty Images)

In Jim Quick’s COVID experience, no political stand was needed to make things complicated enough for him. Many considerations had to be made regarding touring. He turned down some gigs, cut back the band's size for others to make money working in rooms limited to partial seating, but he was not, as I’d been led to believe all musicians were in the age of COVID, completely down and out. Said Quick,

“I got to be honest with you, I've seen a lot of my brothers and sisters in this industry fall during this pandemic, however, our fan base is so huge and so loyal that we would do various online shows and things like that. We'd actually have towns and cities hiring us to come to their studios and do a live performance there just so their community could watch it and they would pay us pretty good money. And they'd get local sponsors and stuff.”

I asked Quick about the number of dates he would typically play pre-COVID and how that changed. He said,

“Last year was around 50. This year we'll probably play between 100 and 150, and normally we play about 250. It's twice as good as last year, but half as good as it normally is.”

Quick explained what industry thinking was about when things might return to normal:

“When I talk to agents in Nashville and the larger booking agencies, I think 2022 is going to be such a madhouse. I feel like 21 is going to be a slow progress. I feel like by the time 22 comes around people are going to be so antsy and people will feel more secure and I feel like we'll have the herd immunity under control because of the vaccination or because people have already had it or whatever.”

Quick and I also had time to speak about beach music and my initial impressions of it.

I want to tell those of you who are fellow disciples of music a bit about beach music, where it comes from, and what I thought it could mean upon first hearing it. In our current politically divisive climate, where contemporary musicians go out of their way to jump on soapboxes and even on Superbowl halftime shows seemingly proselytize for a Luciferian coming New World Order, beach music is another thing altogether. Beach music, having no political affiliation, offers memorable optimism.

Wikipedia, among others, describes beach music as a genre. Quick disagreed,

“A lot of people call it a genre and it's not so much a genre because the music -- beach music really comes from all kinds of different genres; Beach music is more the lifestyle. It pulls from different genres of music but it pulls from the happy side of it. It pulls on the positive, good times side of it. And really, if you think about that, it narrows down to good love, humor -- it could be about cheating but it's normally humorous -- and a lot of alcohol-based songs. Kind of like the old R&B ‘One Mint Julip’ from The Clovers, and then the sexual innuendos from The Dominoes' ‘Sixty Minute Man’ and all these classic songs from the 50s.”

My introduction to beach music came while vacationing in Myrtle Beach in 2019 for just a single day before vacationers such as myself were ordered to evacuate. Parts of the city had to prepare for the touchdown of Hurricane Dorian. In a large lumbering traffic procession headed out of town, I passed time listening to a local station that featured a beach music countdown. They played vintage 60s and 70s pop-soul classics through the intermittent rain such as “Give Me Just a Little More Time” by The Chairmen of the Board, but also contemporary tracks such as Quick’s, who I heard there for the first time.

Music legacy remains strong with Chairmen of the Board

Music legacy remains strong with Chairmen of the Board

I couldn’t define the thing that unified the tracks but knew there was something; There was likely the subject matter as described by Quick, but I also thought of racial harmony, a mix of black and white artists sharing the same general upbeat but not saccharine attitude. Quick outlined the haul from segregated beaches to the beach music scene as it’s existed since the 1970s:

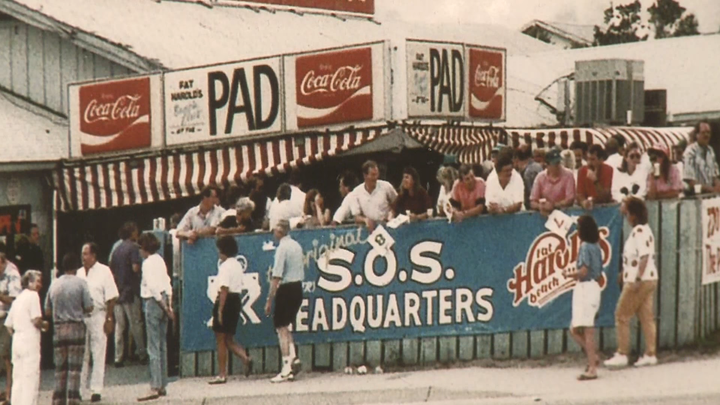

“The way beach music really got started was a lot of these white fraternity kids would go down to the coast for summer break, or spring break, and they were fascinated by the -- the beaches were segregated at that time -- but they would venture over into some of the black clubs, and hang out and watch them dance and listen to the jukebox. Well, they started buying -- back then they called it race music -- and they would buy these 45s and they would demand to play them in the jukeboxes in the clubs that were in the predominantly white places.”

1970's Beach Music And Shag Dancing

1970's Beach Music And Shag Dancing

Despite beach music’s origins in a time of enforced racial division, by the integrated 1970s, black artists were celebrated by beach music fans as musical icons. Quick explained,

“There was integration. Then you had bands that were integrated black and white, and you had this huge influx of white bands that were covering black artists, and then we're working together with artists like General Johnson from the Chairman of the Board who was international. He actually moved out to Charlotte started working record labels and working with these white bands, writing with them, next thing you know it's just hand in hand and they have a Carolina Beach Music Awards ceremony and over time it just became a big melting pot.”

The voracious musical interest of vacationing white fraternity brothers continues, but now on a level playing field with nobody excluded from opportunity or reward. The only division left worth noting may be whether or not you want to get onboard.