For as long as I can remember—at least 40 years—people have been warning about the dire effects of federal spending and the national debt. I can remember my father and uncles sitting around discussing these things. Among conservative pundits and economists, the predictions (again, for 40 years) have been that inevitably out-of-control government spending would result in sharp inflation, even, perhaps, hyperinflation.

With one exception (the period 1970-1980, largely due to energy price increases), these predictions have proven wrong. They have proven wrong so much that hyperinflation has taken on a Second Coming aspect—expected by many, so far seen by none.

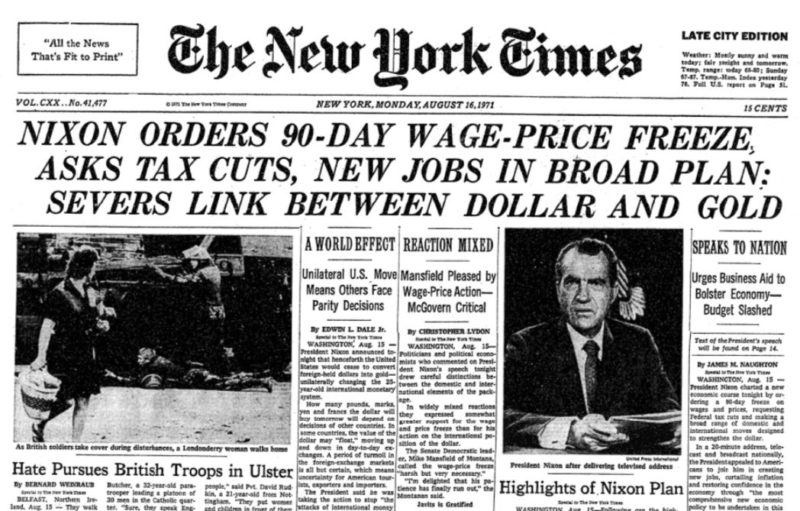

At long last, may that be changing? There have always been canaries in the coal mine of inflation, most notable prices in commodities such as gold, silver, copper, oil, gas, and most critically, labor. If you had bet on gold from 1980 to 2010, you would have bet on a loser. Gold moved up a little (standing today at around $1700 per ounce). Of more interest is the fact that in the last five years, gold jumped $575, and over the last 20 years, $1500. Starting in 1971 when President Richard Nixon ended the fixed exchange gold standard put in place by the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1944, gold sat around $40 an ounce. Four years later, Americans were allowed to privately own gold for the first time since the New Deal and the price rose to just under $200 an ounce. (Somewhere in there, yours truly bought gold for under $200 an ounce and sold for $450 by the late 1970s).

The change in the law allowing private citizens to own gold came as the U.S. was entering its only serious inflationary binge since “Horsemeat Harry” Truman’s post-WW II era. In the early 1970s, in response to the United States assisting Israel in the Six-Day War and Yom Kippur War, Saudi Arabia, and other Muslim oil-producing states cut production and raised prices. At that time, they still largely had the ability to control oil prices. A resulting oil shock sent prices for everything up, with government officials helpless to do anything about it. The hapless Gerald Ford, rather than demanding the head of the Federal Reserve Board, Arthur Burns, crack down on money creation, took his case to the American public with a ridiculous “WIN” (Whip Inflation Now”) button. Predictably, inflation ignored Ford’s button and continued to ravage the administration of his successor, Jimmy Carter. After a year’s tenure as Fed chief, William Miller was replaced by Carter’s appointee, Paul Volcker.

The change in the law allowing private citizens to own gold came as the U.S. was entering its only serious inflationary binge since “Horsemeat Harry” Truman’s post-WW II era. In the early 1970s, in response to the United States assisting Israel in the Six-Day War and Yom Kippur War, Saudi Arabia, and other Muslim oil-producing states cut production and raised prices. At that time, they still largely had the ability to control oil prices. A resulting oil shock sent prices for everything up, with government officials helpless to do anything about it. The hapless Gerald Ford, rather than demanding the head of the Federal Reserve Board, Arthur Burns, crack down on money creation, took his case to the American public with a ridiculous “WIN” (Whip Inflation Now”) button. Predictably, inflation ignored Ford’s button and continued to ravage the administration of his successor, Jimmy Carter. After a year’s tenure as Fed chief, William Miller was replaced by Carter’s appointee, Paul Volcker.

Whether it was Carter refusing to pressure Volcker to act, or whether Volcker thought that tightening the money supply would saddle Carter with a depression—and hence took it on himself not to act— is unclear. Regardless, the money spigot stayed open. Home mortgage rates were in double digits; credit card interest rates were over 25%. Fuel prices remained locked only because Ford and Carter had capped the price of oil and gas. All this did was drive people into a frenzy to get gasoline. States desperately tried a variety of measures to ensure people got gas, including “even/odd” sale days where people with even-numbered license plates could buy on MWF, odd-numbered plate holders could buy on TTHS, and all stations were to be open only from 8:00 am to 5:00 pm and closed on Sundays. I personally suffered from this once while, in my rock band, traveling to a gig in Colorado. We had taken a (stupid) scenic route through New Mexico, suddenly finding ourselves on fumes in the metropolis of . . . Why. (Yes, there is a Why, New Mexico, and you'd understand the name if you’d been there.) We were five minutes too late and had to sit outside a gas station all night in the snow, turning on the van just long enough to keep from freezing until 8:00 the next morning.

Whether it was Carter refusing to pressure Volcker to act, or whether Volcker thought that tightening the money supply would saddle Carter with a depression—and hence took it on himself not to act— is unclear. Regardless, the money spigot stayed open. Home mortgage rates were in double digits; credit card interest rates were over 25%. Fuel prices remained locked only because Ford and Carter had capped the price of oil and gas. All this did was drive people into a frenzy to get gasoline. States desperately tried a variety of measures to ensure people got gas, including “even/odd” sale days where people with even-numbered license plates could buy on MWF, odd-numbered plate holders could buy on TTHS, and all stations were to be open only from 8:00 am to 5:00 pm and closed on Sundays. I personally suffered from this once while, in my rock band, traveling to a gig in Colorado. We had taken a (stupid) scenic route through New Mexico, suddenly finding ourselves on fumes in the metropolis of . . . Why. (Yes, there is a Why, New Mexico, and you'd understand the name if you’d been there.) We were five minutes too late and had to sit outside a gas station all night in the snow, turning on the van just long enough to keep from freezing until 8:00 the next morning.

First Day of Gasoline Rationing 1978 - 1979 (Bettmann/Bettmann/Getty Images)

First Day of Gasoline Rationing 1978 - 1979 (Bettmann/Bettmann/Getty Images)

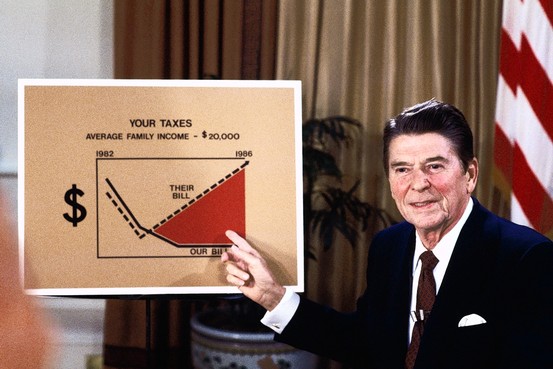

None of these measures worked. There were massive lines in New York City around the blocks of cars waiting to top off their tanks; there were fistfights as people cut in line; and worse. Although the man-made shortages were alleviated in time, it wasn’t until Ronald Reagan arrived in 1981 and immediately strong-armed the Saudis and their friends that prices fell. Equally important, Reagan became president, and he retained Volcker, telling him to whip inflation NOW. He didn’t mean it as a slogan. Volcker tightened the screws, and by 1982 the nation was in a severe depression.

But it worked. By mid-1982, Volcker reported to Reagan that the inflation rate for that quarter was zero!! Reagan/Volcker had brought the inflation rate down from over 8% to zero in a year and a half! Reagan’s economy hummed, but without the predictable inflationary surge that was supposed to go along with it.

No doubt Reagan—and every successive president, including Donald Trump—could do nothing about deficits and the national debt. During Reagan’s second term, Democrats feigned concern over the deficits, so much that they convinced Dutch to agree to a deal: certain tax increases (then known as “loopholes”) in return for budget concessions by the Democrats that would lead to a balanced budget. Of course, taxes went up, but the budget was never, ever cut. Indeed, the Democrats learned a neat trick at this time: they began to charge than a cut in the rate of growth of a program was a “cut” in the program. Such is Democrat logic and the willingness of the Hoax News media, even then, to believe them.

It is worth noting that just as Reagan took office, two important economists, Robert Eisner and Paul Pieper, in 1984 published an article called “A New View of the Federal Debt and Budget Deficits” in the prestigious American Economic Review noting that our entire notion of measuring the “national debt” was likely off. For example, Eisner noted, the price of federal assets was by law fixed at the price Uncle Sam paid for them. Let’s take our gold example: the government bought gold at $15 an ounce. Yet when Eisner wrote, gold was worth $400-600 an ounce. That’s an increase of 3,900%! Or consider the value of federal land: at the time Eisner wrote, the United States owned the San Francisco naval base called “The Presidio.” It was a phenomenally expensive territory yet was valued on the books as whatever the government bought it for. Based on this, Eisner concluded that the national debt in the mid-1980s, officially at $1.8 trillion, was closer to about $200 billion. Of course, as the saying went, “A billion here, a billion there, and soon you’re talking real money,” but that was still orders of magnitude less than what the stated U.S. national debt was.

It is worth noting that just as Reagan took office, two important economists, Robert Eisner and Paul Pieper, in 1984 published an article called “A New View of the Federal Debt and Budget Deficits” in the prestigious American Economic Review noting that our entire notion of measuring the “national debt” was likely off. For example, Eisner noted, the price of federal assets was by law fixed at the price Uncle Sam paid for them. Let’s take our gold example: the government bought gold at $15 an ounce. Yet when Eisner wrote, gold was worth $400-600 an ounce. That’s an increase of 3,900%! Or consider the value of federal land: at the time Eisner wrote, the United States owned the San Francisco naval base called “The Presidio.” It was a phenomenally expensive territory yet was valued on the books as whatever the government bought it for. Based on this, Eisner concluded that the national debt in the mid-1980s, officially at $1.8 trillion, was closer to about $200 billion. Of course, as the saying went, “A billion here, a billion there, and soon you’re talking real money,” but that was still orders of magnitude less than what the stated U.S. national debt was.

In other words, the answer to “why no inflation” may lie somewhere other than purely monetary expansion. For example, economic historian James Gordon has recalculated the entire consumer price index for the periods up to the 1990s and found that the indices substantially under-counted real growth and couldn’t count at all value provided to human lives with traditional statistics. Just as an example, while long-standing measures of the increased value of the light bulb over candles or kerosene lamps were measured in price, the light bulb's actual illumination power and its longevity were vastly greater. Also, the elimination of indoor kerosene vapors made human health better (people lived longer) and saw more clearly. None of these factors were ever measured in traditional statistical analysis. Now spread that across the board for hundreds of thousands of products…

In other words, the answer to “why no inflation” may lie somewhere other than purely monetary expansion. For example, economic historian James Gordon has recalculated the entire consumer price index for the periods up to the 1990s and found that the indices substantially under-counted real growth and couldn’t count at all value provided to human lives with traditional statistics. Just as an example, while long-standing measures of the increased value of the light bulb over candles or kerosene lamps were measured in price, the light bulb's actual illumination power and its longevity were vastly greater. Also, the elimination of indoor kerosene vapors made human health better (people lived longer) and saw more clearly. None of these factors were ever measured in traditional statistical analysis. Now spread that across the board for hundreds of thousands of products…

More recently, people have puzzled as to why, with a $27 trillion national debt (with a GNP of $21 trillion) we haven’t seen Weimar-Republic-style hyperinflation. The answer may well lie with the Eisner/Gordon analysis. But there is one more element to consider. George Gilder’s titanic Wealth & Poverty cited an amazing study by Sir Henry Phelps Brown and Sheila Hopkins of inflationary trends over a 600-year period. Instead of the “mountain range” of price increases and decreases, they were surprised to find a stair step of substantial price increases at key moments in western history, followed by a flat “step” for decades, even a century. What was going on? They found the “steps” correlated with massive reorganizations in western economic society—the Commercial Revolution, the Capitalist Revolution, the Industrial Revolution, and most recently, the Computer Revolution. Phelps Brown and Hopkins had only just caught the very beginning of the Computer Age. Currently, the advances in productivity from computers is totally and completely incalculable by economists with their pre-computer level tools, and I am convinced they are still trying to measure the “productivity growth” of the computer revolution with failed concepts and models.

Traditionally, one would look at a rotary dial phone in, say 1970, and then a new model in 1975 and measure performance increase + price improvement = value (again, I won’t be stating this in “economese”). This worked as long as you were comparing apples to apples. But the cell phone (sticking with just this example) changed all that. It’s not just a “better phone.” It’s a better phone x 1000 PLUS a computer PLUS a GPS, PLUS a gaming device PLUS a camera PLUS an e-mail system PLUS PLUS PLUS. I can’t even imagine all the functions of a phone, let alone use them all. That’s the point. Neither can economists. The “value” of a cell phone cannot even begin to be contemplated because it is a unique device. A steamship replaced a sailing ship. Easy to calculate. But imagine if the steamship replaced the buggy, the sailing ship, the scales in the grocery store, the chessboard, the abacus, on and on?

We have been in a genuine, unprecedented productivity revolution (especially in medicine, where some prices are reflecting it) for 35 years, and money/valuations have not caught up. It’s a nearly bottomless pit that all the QE whatevers still can’t adjust to. We see it in “green” technologies incorporated into homes, into roboticization in all sorts of domestic devices. A coffee maker with a timer is no longer just a coffee maker but an alarm clock. My television links into the web for Amazon Prime or to my ancient Sega Dreamcast. All discussions about productivity are more or less irrelevant until we actually can figure out how deeply in the philosophical hole we are in defining productivity increases. In my view, we are likely 25 years behind the curve, meaning that the productivity increases are so far off the charts that I am writing to you while getting messages on my cell phone while a timer sets my coffee while automatic air conditioning adjusts my energy levels . . . etc. In other words, my personal productivity has increased 100-fold.

We have been in a genuine, unprecedented productivity revolution (especially in medicine, where some prices are reflecting it) for 35 years, and money/valuations have not caught up. It’s a nearly bottomless pit that all the QE whatevers still can’t adjust to. We see it in “green” technologies incorporated into homes, into roboticization in all sorts of domestic devices. A coffee maker with a timer is no longer just a coffee maker but an alarm clock. My television links into the web for Amazon Prime or to my ancient Sega Dreamcast. All discussions about productivity are more or less irrelevant until we actually can figure out how deeply in the philosophical hole we are in defining productivity increases. In my view, we are likely 25 years behind the curve, meaning that the productivity increases are so far off the charts that I am writing to you while getting messages on my cell phone while a timer sets my coffee while automatic air conditioning adjusts my energy levels . . . etc. In other words, my personal productivity has increased 100-fold.

And there are other factors that few people have quantified. Amar Bhide, in The Venturesome Economy, notes that increasingly, the role of research and development (R&D) has been abandoned or minimized by companies such as Apple or Samsung because they just don’t need it. R&D used to help companies define their next products or services, but Bhide points out that today consumers do that for the companies. All Apple has to do is ask its phone users what new application they want to see, and they will get thousands of responses. Thus, corporate R&D may be low in the traditional sense, yet new products and services are increasing geometrically. Again, traditional valuations have not accounted for this. There is a final element to watching inflation and that is that while people focus on the quantity of money, there is little attention paid to the other key factor, the velocity of money. Right now, velocity is still fairly stable. Increasing velocity of money suggests that people are anxious about the value of a dollar, and hence unload it for a product as soon as possible. No currency in the world currently can even contemplate replacing the dollar as the unit of exchange. Far from becoming a "currency" that is used in exchange itself, bitcoin has become a form of savings—the new gold. In Weimar Germany, housewives went to their husbands' factories to get paid daily in cash, hurrying to the store before prices rose yet again. There is no evidence of any concern about inflation based on velocity behavior.

Panic of 1857

Panic of 1857

Illustration depicting a run on the Seamen's Bank during the Panic of 1857.

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

So, are the recent price increases in commodities and energy reflective of a new age of inflation? Possibly. Keep your eye on that critical indicator, wages. So far, there has been no wage inflation, while copper and oil prices are heavily subject to political factors currently afflicting the markets. (It is worth noting that one of the worst depressions in American history, the Panic of 1837 was entirely due to the sudden drying up of Mexican silver—which was a reserve for bank money at the time; or that the Panic of 1857 was started by the Supreme Court Dred Scott decision ensuring that slavery spread to the territories, causing railroad stocks to crash). Ultimately, until we find a way to measure the productivity growth associated with computers (which Gordon has not done yet), it may be impossible to determine truly what our national debt is.